Mariya Ivancheva (University of Strathclyde) is a sociologist and anthropologist of higher education and labour, whose research focuses on the precarisation, digitalisation and outsourcing of academic work, and the role of university communities in large-scale processes of political and social change. She is the author of the monograph The Alternative University, lessons from Bolivarian Venezuela (Stanford UP 2023) as well as articles about Venezuelan higher education reform, left-wing students and intellectual movements, housing provision, and migration to Argentina. She has been involved in left-wing and feminist initiatives and publications in East Central Europe like LeftEast, Levfem and the East European Left Media Outlet (ELMO).

We recorded this interview via Zoom, as part of the PLATZFORMA podcast.

An audio version of the interview can be listened on Spotify.

Vitalie: Mariya, can you tell us a bit about your relationship to Venezuela? You did fieldwork and wrote a book, The Alternative University, lessons from Bolivarian Venezuela. What was your research focused on, and how does it shape your understanding of Venezuela today?

Mariya: Thank you for the invitation, and hello to Vitalie and to the audience of Platzforma. I am an anthropologist and sociologist of higher education and labor. I currently work at the University of Strathclyde in Glasgow, and my interest in Venezuela began during my PhD studies at the Central European University in Budapest. At that time, I became interested in comparing two very different higher education projects: the Central European University, on the one hand, and the Bolivarian University of Venezuela, on the other.

The Central European University emerged out of the socialist transition in East-Central Europe and was primarily aimed at the middle classes. Its goal was to train political and policy elites for the new post-1989 states. It was strongly shaped by global norms of higher education, including prestige, publication in English, and integration into international academic circuits.

At the same time, Venezuela was undertaking an almost reverse experiment. It sought to massify an otherwise elite higher education system. This reform was strongly informed by socialist intellectuals, many of whom had been militants under what is now known as the Fourth Republic (1958–1998), the period preceding Hugo Chávez’s Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela. Despite being labeled a democracy, this period functioned in many ways as a police state that actively repressed the left. Some of the leftists from that era later joined Chávez’s project and played a key role in efforts to expand access to higher education.

I went to Venezuela in 2008 to study this socialist experiment, which aimed to provide education and employment opportunities to the poor majority of Venezuelan citizens. In subsequent years, I also conducted research on housing policy, focusing on the Gran Misión Vivienda, particularly in comparison with socialist-era housing policies in Bulgaria that targeted poor populations, especially the Roma. Later, just before and during the pandemic, I began a new project involving some of my former research participants and other highly educated Venezuelans who had migrated after 2014 and were living in Buenos Aires. I carried out an ethnographic study of this group as well. My most intensive period of residence and research in Venezuela was between 2008 and 2011, during the height of Chavismo, while Chávez was still alive.

Throughout this time, I have followed the various routes into and out of Bolivarianism, and the trajectories of Bolivarian socialism, as experienced by people who were, at least initially, involved in the project.

Vitalie: Venezuela has returned to global headlines after Trump’s abduction of Maduro, but many people lack historical context for the indictments and rhetoric involved. You lived in Venezuela during the later period we call now Chavismo. What was Chavismo historically, and what—if anything—remains of it today?

Mariya: Chavismo was a controversial and highly eclectic political period and orientation. Historically, it can be traced back to what is often described as the first major protest against neoliberalism in the region: the Caracazo of 1989. This was a popular uprising against the adoption of Washington Consensus policies and, in particular, against increases in domestic gasoline prices. The protests ended in a brutal repression that resulted in the deaths of many citizens, especially in Caracas.

During this period, a group of military officers—including Hugo Chávez and others such as Diosdado Cabello—were deployed to investigate left-wing movements that had remained underground despite the formal end of dictatorship in the 1950s. Through this process, they began to recognize what they saw as strategic thinking and moral legitimacy within the left, and to contrast it with an establishment that was deeply elitist, strongly pro-American, and unwilling to redistribute the country’s oil rents to the broader population. When Chávez led a failed military uprising in 1992—variously described as a rebellion or a coup—it nevertheless signaled that at least part of the armed forces was adopting a nationalist, patriotic, and populist stance oriented toward redistribution and social justice.

When Chávez came to power in 1998, roughly a decade after the Caracazo, he was not yet a full-fledged socialist. However, he was gradually recognized by former left-wing guerrillas and established leftist parties as a potential ally. He was a nationalist, religious, and a military figure—three characteristics that traditionally provoke skepticism on the left. Yet many of the laws enacted during his early presidency, particularly around 2001, clearly favored redistribution and social justice. These reforms addressed fisheries, education, and the oil sector.

There has been considerable speculation, particularly in recent years, that the Trump administration sought to reverse the nationalization of Venezuelan oil allegedly carried out under Chávez. This is incorrect: Venezuela’s oil industry was nationalized in the 1970s. What is true, however, is that early Chavista reforms increased the participation of Venezuelan companies in oil exploitation. Prior to this—and, sadly, largely continuing today—Venezuela’s heavy crude oil was extracted and sold directly to foreign companies, often U.S.-based firms such as Chevron.

These reforms were relatively mild, but their significance lay in fostering greater class consciousness and a stronger sense of national interest. Importantly, this was not nationalism in a narrow sense. Through Chávez’s engagement with internationalist guerrilla movements and left-wing organizations within and beyond Venezuela, it became clear that Bolivarian socialism could have a broader regional and global impact. It could reshape relations with existing socialist societies such as Cuba, foster continental alliances addressing the shared histories of indigenous dispossession and slavery, and rethink Latin American political economy beyond U.S. imperial ambitions and broader forms of neocolonial domination.

Within Chavismo, there thus emerged an increasingly explicit narrative and set of reforms oriented toward socialism—of a particular kind. This was not revolutionary socialism, but rather a form of radical social democracy, marked by a strong commitment to redistribution and, at least initially, to economic diversification. The aim was to reduce dependence on oil and move beyond an exclusively extractive model of development that had long characterized Venezuela and much of the region.

Vitalie: I want to make a parenthesis. We’ve repeatedly used terms like Bolivarian, Bolivarianism, and Bolívar. Could you briefly explain the role of Simón Bolívar in Chavismo, and how his figure was reinterpreted to serve the project?

Mariya: This wasn’t a very easy subject and I don’t think a lot of works in English on Bolivarian Venezuela, including my own book on the Bolivarian higher education reform, discuss in great length this very complex relationship.

Simón Bolívar was never an unambiguous historical figure. He was a—likely narcissistic—member of the criollo elite. He held controversial views about who should rule the liberated South American subcontinent: namely, himself and other men of his military rank, upper-class position, and white racial background. At the same time, he articulated a vision of a united South America governed through a loosely federal and autonomous system, independent from its former colonial powers. This aspect of his thought has often been interpreted as anti-imperialist—or, with considerable interpretive stretching, even anti-capitalist—particularly when read in conjunction with figures such as José Martí in Cuba.

Whether such interpretations are fully justified remains an open question. What is clear, however, is that Bolívar has played a powerful symbolic role in Venezuela. His political project was launched from Venezuelan territory and assigned the country a central place in the imagined construction of a new continental polity. This internationalist dimension later became especially important for Chavismo. As a result, many of Bolívar’s more controversial historical positions were subsumed under what were seen as his potentially progressive traits.

Within the Bolivarian canon of Chavismo, two additional figures are usually mentioned alongside Bolívar: his military mentor Francisco de Miranda, and his tutor Simón Rodríguez, also known as Samuel Robinson. Rodríguez, in particular, is frequently cited in educational discourse. While educators often invoked his ideas as foundational for Bolivarian educational reform, it is difficult to trace how his pedagogical philosophy was concretely translated into everyday teaching practices. What mattered symbolically, was that his alias, Robinson, was given to the national literacy campaign (Misión Robinson), signaling a commitment to education for the poor.

In this way, Bolivarianism became closely associated with education—not only formal schooling, but a broader vision of the state as an educating entity, or estado docente, a term widely used during the Bolivarian process. Concepts drawn from the eclectic ideological repertoire of Bolivarianism were thus placed in dialogue with Chávez’s own articulation of “socialism of the twenty-first century.” While this synthesis often functioned effectively on the ground, its intellectual and historical origins are far more complex than is usually acknowledged, and they require further critical examination.

Vitalie: Staying with Chavismo but moving away from geopolitics and economics: oil revenues were central to financing social transformation. Could you talk about the social missions you know best—particularly in education and housing—and how were they financed and how did they function in practice?

Mariya: Sure. Another crucial moment, not yet mentioned, was the failed coup d’état against Chávez in 2002, which involved documented participation by the United States and was coordinated domestically by the Chamber of Commerce (FEDECÁMARAS). The coup did not ultimately succeed, and Chávez returned to power through massive popular mobilization. The following year, in 2003, a general strike was organized by senior managers and engineers within the national oil company, PDVSA. This event made clear to Chávez and his supporters that they had few allies among the upper echelons of the country’s knowledge and technical elites—and that it was politically and economically unsustainable if a single company could paralyze the national economy.

In response, the government gradually developed a series of social policies known as misiones—“missions,” a term with clear religious connotations—aimed at redistribution and social justice. Some of these focused on primary healthcare, most notably Misión Barrio Adentro, which has been extensively analyzed by scholars such as Amy Cooper. Others addressed social assistance for mothers, welfare benefits, and state-subsidized food distribution, later institutionalized through Mercal. In education, the missions included Misión Robinson for literacy, Misión Ribas for secondary and vocational education, and Misión Sucre, later expanded through Misión Alma Mater, for higher education. The housing program Gran Misión Vivienda was introduced later, after severe flooding in 2010 left more than 300,000 people around Caracas homeless.

These initiatives were initially funded through oil revenues, which covered salaries, infrastructure, and basic operational costs. In healthcare, for example, most early investments went toward establishing basic general practitioner clinics in the barrios, where even minimal medical services had previously been absent due to privatization or chronic underfunding of public hospitals. However, these clinics initially lacked diagnostic and specialized services, which remained concentrated in under-resourced hospitals. This created significant tensions among hospital-based doctors and nurses. By the time Barrio Adentro II (diagnostic services) and Barrio Adentro III (specialized hospital support) were introduced, many healthcare workers were already disengaging from or even actively sabotaging the process, while others chose to emigrate.

Similarly, in higher education. basic university-level education was extended to more than half a million people who would never have had access under the previous system. Yet access to traditional university campuses remained limited, and many students studied locally in remote classrooms in schools, nurseries, squares, and living rooms in their villages or neighbourhoods. This was not officially framed as a deficiency, since the government promoted a decentralized education model inspired by distance-learning institutions such as the UK Open University rather than residential universities. Nonetheless, these local centers required qualified staff and recognized accreditation. For a long time, accreditation authority remained in the hands of traditional public universities dominated by opposition supporters. As a result, Bolivarian higher education institutions were widely perceived as ‘second-class’ and struggled to secure credentials for their faculty and formal recognition for their programs.

At the same time, higher education suffered from a broader problem that affected many policy areas: constant institutional instability. Programs were launched and then rapidly restructured or abandoned; administrators were reassigned to new missions; and funding was frequently redirected toward emerging political priorities. This lack of continuity undermined institutional development. Even when educators invested enormous time and effort into building new programs, they were often paid less, faced fewer opportunities for promotion, and lacked job security compared to staff at traditional public universities, which continued to receive greater funding.

By the time of my fieldwork, many educators within the Bolivarian system—often themselves from poor urban or rural backgrounds—had become disillusioned with Chavismo and left the country. I later encountered several of them in Argentina during my research on highly skilled Venezuelan migrants working in the platform economy during the pandemic. Many were deeply frustrated with how ‘socialism’ was implemented in Venezuela. While many of them did not support the political opposition, most were dissatisfied with the loss of upward mobility for themselves and their students.

A similar ambivalence characterized the Bolivarian government’s housing policy. Gran Misión Vivienda produced millions of housing units—an unprecedented achievement in recent Venezuelan history. Yet for many people squatting in downtown high-rises and pockets of self-build barrios with already established infrastructure, these interventions came too late or required relocation far from their original home, forcing them to rebuild their lives in areas lacking infrastructure, social networks, or collective memory. Large- scale supporting infrastructure projects were often abandoned. For example, despite signed contracts and later narratives emphasizing Chinese involvement, a planned cross-country railway never materialized under Chavismo. In this sense, projects driven by inclusive intentions frequently fell short of their promises—not only because of opposition sabotage, but also due to mismanagement within the Chavista state itself.

Perhaps the most significant failure concerned economic diversification. Numerous initiatives sought to promote local food production and other forms of non-oil economic activity, aiming to reduce dependence on Venezuela’s oil-based “Dutch disease” economy. However, except that large-scale companies and land-owners were resistant to give their unused land or sell their entreprises to the state, on the side of the state even the policies encouraging the mass population toward diversification were fragmented and easily abandoned in the face of even minor resistance.

Cooperative workers, for instance, described growing vegetables only to have their produce purchased at subsidized prices by intermediaries and then resold to them at several times the original cost. Many diversification efforts also depended on credit from so-called “popular” or “communal” banks. Yet accessing these funds required complex bureaucratic applications, which often advantaged opposition supporters with greater educational and administrative skills.

Finally, state-led initiatives frequently began and ended abruptly, with little explanation. Cooperatives might be instructed to sew red T-shirts for the revolution, only to be redirected shortly afterward toward community gardening or another priority altogether. Communities were repeatedly forced to realign their labor and expectations, often within the span of months. This pervasive short-termism significantly undermined economic sustainability and social trust, well beyond the effects of opposition sabotage alone. And every time that one of these projects or lines malfunctioned Venezuela could always fall back on oil. And that’s why oil became — or rather remained — the single crop of a Dutch disease economy, that was still attractive for such a major resource grab by the US, despite otherwise crumbling infrastructure.

Vitalie: Thank you for complicating the common narrative that Chavismo simply collapsed when oil prices fell—as if socialism only works while money lasts. Your account highlights internal opposition, short-term policymaking, and improvisation. Before turning fully to Maduro, I want to stay briefly with Chavismo itself. Maduro presented himself as Chávez’s heir, yet your 2016 FocaalBlog piece pointed to major contradictions: popular mobilization alongside accusations of hyper-leadership, revolutionary hierarchy, and the rise of Boligarchs. How did participatory democracy and strong military-style leadership coexist within Chavismo?

Mariya: The issue of boligarchs—or the boliburguesía (the Bolivarian bourgeoisie), comparable to what in Serbia is called the crvena buržoazija, the “red bourgeoisie”—is central. As in other socialist experiments, such a group coexisted with the Bolivarian project in ways that were perhaps unsurprising, though not without significant contradictions and convulsions. It is somewhat cliché to note that Venezuela has a long history of caudillismo—what in Eastern Europe we once described as powerful local barons, and what we now often label oligarchs.

But back to your main question. This is a difficult question, and scholars have approached it differently depending on their positionality in the field. Researchers working closely with radical grassroots collectives in the barrios—for example, Geo Maher—have often interpreted Chávez not as the progenitor or sole leader of the process, but as a byproduct of a broader popular movement that both preceded and exceeded him. From this perspective, the Bolivarian project was less about Chávez as an individual and more about popular democracy, sovereignty, and forms of dual power.

By contrast, many international journalists and researchers who primarily engaged with foreign-educated, affluent elites in certain areas of Caracas produce a very different narrative. In those circles, there was strong class-based aversion toward Chávez and complete rejection of his leadership. Mostly they called him totalitarian, but even those with leftist ideas found ways to critique his alleged failure to conform to ideals drawn from “pure” socialist or anarchist theory.

My own research, which followed mostly groups involved in higher education and housing, revealed a persistent and unresolved tension within Chavismo: on the one hand, the strong masculine charisma of its leadership—whether embodied by Chávez or later by Maduro—and, on the other, the everyday labor of the revolution carried out predominantly by women activists. It is telling, in this regard, that Chávez chose Maduro rather than, for example, Cilia Flores—then president of the National Assembly and his legal counsel after the 1992 rebellion, now better known as Maduro’s wife—as his successor.

Yet on the ground, the Bolivarian process was overwhelmingly sustained by women, often single mothers in working-class communities. Importantly, these women did not generally experience their role with bitterness. On the contrary, the Bolivarian project granted them an unprecedented sense of agency and political recognition. For the first time, many were acknowledged as legitimate political actors, actively shaping a more equitable future for their children and their communities.

Perhaps most importantly, while much research has focused on these active and mobilized groups, a growing segment of the population remained largely underexamined in the Chavista era, and are now mostly visible through the lens of migration research. This is the expanding group of people who became increasingly disenfranchised by the Bolivarian process—those who felt that the promise of the oil state failed to deliver the benefits they believed they were entitled to as citizens. Part of this group came from the middle classes, who perceived that the upward mobility once promised through higher education and skilled employment would not materialize within the socialist project.

Other substantial segments consisted of the Bolivarian activists who remained loyal to the system; and of the poorest of the poor—people I encountered during my research on housing, particularly when accompanying university groups into the most marginalized communities. To explain these two groups, Caracas offers a particularly vivid illustration. In several barrios where I conducted research on both higher education and housing, one could observe an almost graphic form of class-based spatial zoning. As one climbs the hillsides from the base—where shared taxis stop or staircases begin—into the terraced neighborhoods above, levels of infrastructure, political incorporation, and state presence gradually diminish.

The lower sections of the hills, where barrios were first established and where infrastructure had been built through earlier protest movements or Bolivarian interventions, tended to show strong political alignment with the socialist party and great access to state support. As anthropologist Matt Wilde’s work vividly illustrates with a case study outside Caracas, for families in such areas, Bolivarian reforms produced tangible structural changes and real upward mobility. Such families often remain loyal to the regime even today, though that loyalty is less ideological and more clientelistic. Here, parallels can be drawn with analyses by Ilya Budraitskis on contemporary Russia, as well as scholarship on Hungary, Serbia, and other contexts where patron–client relations shape political loyalty. In such cases, allegiance to the governing elite may originate in political commitments but ultimately transcend or even contradict formal politics. These groups continue to form a crucial social base that sustains the regime.

The situation changes markedly higher up the hills. The further one moves from the base, the less infrastructure is available and the fewer state resources reach residents. I became acutely aware of this during the devastating floods of 2010, when many of the most precarious homes in the upper barrios were destroyed. Together with Stefan Krastev, I encountered numerous Venezuelans who had little knowledge of—or had never accessed—the Bolivarian missions until they were relocated to refugios, the temporary shelters established by the government after the floods. To the government’s credit, such emergency responses contrasted sharply with those of neighboring countries, where displaced populations often received little or no assistance. Many residents were eventually granted access to social housing, education, and healthcare. Yet the fact that so many people were previously unaware of these programs underscored how difficult it had been for Bolivarian activists and institutions to penetrate historically marginalized, violent, and poorly serviced communities.

When Venezuela’s humanitarian crisis later intensified, many residents of this latter group—who had never felt genuinely empowered or politically incorporated—also chose to migrate. Most crossed borders into Colombia or Brazil, while others later attempted the perilous journey to the United States through Central America. Today, many of these migrants find themselves in conditions of extreme precarity and exploitation. Estimating the size of this group remains difficult: many were undocumented, some were repatriated—particularly during the pandemic due to severe mistreatment abroad—and official data remain incomplete, even though the Maduro government has made greater efforts in recent years to address the issue and provide identification documents.

Vitalie: Current estimates suggest around 8 million Venezuelans—up to a quarter or even a third of the population—now live abroad, something I can relate to coming from Moldova where our government has no exact count of Moldovans living outside the country’s boundaries. But this sets the stage for Maduro. He was not the obvious successor when Chávez died in 2012, yet Chávez designated him. Maduro was criticized for lacking higher education, but he did have experience as a union organizer and political operative. How do you understand Maduro as a political figure, and how did Chavismo evolve or adapt under him amid changing economic, political, and international conditions?

Mariya: I should begin with a caveat: I am less well positioned to speak authoritatively about developments under Maduro, as I have not returned to Venezuela since he came to power. This is partly due to the precarity of my own academic career, which required me to shift my research focus to other contexts—such as Ireland, South Africa, the UK, and, as always, Bulgaria and Eastern Europe. It is also because, for a significant period, the situation in Venezuela resembled a low-intensity civil war, and many people I knew were fleeing the country. From a research perspective, my work was effectively bounded by a natural policy break around 2010, albeit I did update my book in 2023. That said, I have continued to follow developments closely: through the news, through sustained contact with friends and former research participants, and through my own research with Venezuelan migrants in Argentina during the pandemic. From these vantage points, several key issues stand out.

One of the most significant was the introduction of U.S. sanctions, particularly targeting oil revenues and food imports. At a certain point, Venezuela was facing something close to an effective embargo. Even if one does not go that far analytically, the sanctions represented a severe constraint on the country’s trade autonomy. Companies withdrew, others refused to comply with government directives aimed at mitigating the humanitarian crisis, and the overall effect was to drastically limit state capacity. In this context, Maduro—who emerged as Chávez’s successor, allegedly with Fidel Castro’s endorsement—rapidly lost political legitimacy. He faced repeated challenges, including what amounted to an attempted coup led by Juan Guaidó, while simultaneously trying to keep the economy afloat under constant U.S. pressure. And although some commentators have been dismissive of Venezuelan claims of U.S. interference as conspiratorial, subsequent events have confirmed many of the long-standing suspicions held by successive Venezuelan governments since the beginning of Chávez’s rule. Under these conditions, Maduro increasingly relied on the military and paramilitary forces, granting them substantial power over the distribution of resources, particularly food. This shift facilitated widespread hoarding, speculation, corruption, and the consolidation of clientelist relationships between the highest levels of the state and various military hierarchies.

At the same time, political repression intensified in what I see as a clear break with the Chavista period. During Chávez’s presidency, I could observe that political opposition was neither physically repressed nor fully silenced in the media. Opposition groups operated private media outlets, and although some licenses were not renewed—a move often globally decried as repression—pluralism remained relatively intact. Under Maduro, however, numerous credible accounts point to systematic repression, including physical violence against opposition figures and dissenters—not only from the right, but also from within the Chavista left, including union leaders and Indigenous activists. And while the opposition in exile often presents itself as the sole source of political legitimacy, it is important to note that several left-wing parties were also targeted. These included the Communist Party of Venezuela (PCV), an unreformed Stalinist formation, as well as other left-of-center projects that were intervened with by Maduro’s repressive apparatus.

Whereas Chavismo was characterized more by self-censorship—often justified by the need “not to arm the enemy”—under Maduro, censorship, violence, and coercive force returned more overtly.

I emphasize “returned”. Political violence and repression, particularly against the left, are deeply embedded in Venezuelan and broader Latin American political history. Repression did not start under Maduro, it was renormalized. Just this time it happened in the context of a left-wing government, whereas traditionally political violence in Latin America is directed against the left. In this respect, Chavismo itself was an exceptional period for the history of Venezuela. The much-celebrated liberal democratic period prior to Chávez functioned in many ways as a repressive police state, closely aligned with U.S. interests, with intensive CIA involvement. Student leaders, guerrilla militants, and left-wing activists were routinely persecuted, imprisoned, tortured and killed, and mass graves continue to be discovered today. From a sociological perspective, this history matters when we consider societal thresholds of tolerance for political violence—even when people do not actively support it.

This historical dimension is particularly relevant in understanding the rise of political figures such as Delcy Rodríguez and her brother Jorge Rodríguez. They come from a family of left-wing militants, and their father beaten to death by the secret police, the DISIP (Directorate of Intelligence and Prevention Services)—an institution that, ironically, the Rodríguez siblings now effectively oversee in its successor form. This lineage helps explain the depth of antagonism toward the historical enemies of the left. Such sentiments are neither easily dismissed nor easily forgotten, and they must figure into any serious discussion of contemporary Venezuelan politics. It does not help explain, however, why the Rodriguez siblings and other key figures in Maduro’s government are willing to collaborate with the US except to prevent bloodshed…

Returning to Maduro, there has been considerable debate within the global left about the extent and nature of redistribution under his government. My reading is that, in attempting to preserve political legitimacy, Maduro was caught between powerful interest groups, emerging oligarchs, and entrenched elites, leaving him with very limited resources to redistribute. Such tensions would strain even a functioning and diversified economy. In Venezuela’s case, they unfolded within an increasingly stagnant, single-’crop’ economy, one in which even investment in oil extraction infrastructure appears to have been neglected. And yet, it is important to acknowledge that Maduro’s government performed comparatively better than many others during the pandemic. Cash transfer schemes, food subsidies and housing provision continued despite extreme constraints. The key failure, however, appears to have been the inability to sustain political legitimacy—not only among disenfranchised groups, but also among core allies and client networks key to enable redistribution and maintain social cohesion.

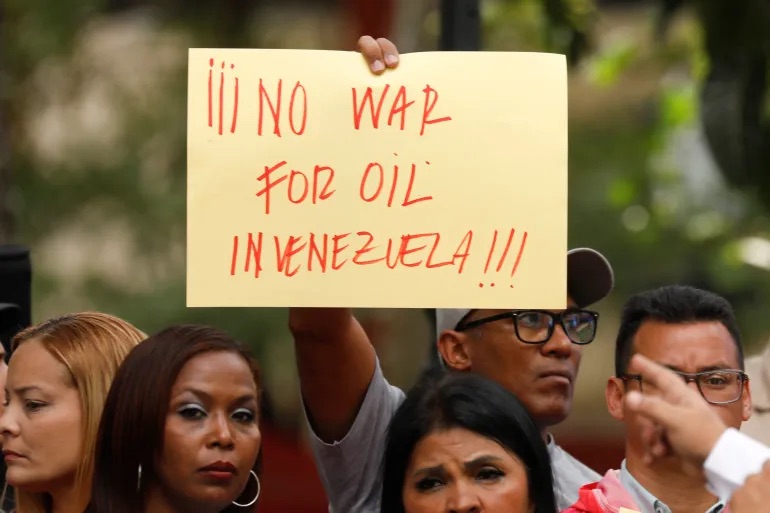

This brings us to the present moment. We are now witnessing protests within Venezuela against what many perceive as an extraordinarily aggressive and unprecedented power grab by Trump—not only against Maduro, but against Venezuela’s political sovereignty itself. While there have been demonstrations demanding Maduro’s physical return to the country, I have seen far less support for his continuation in power. Many Venezuelans would have welcomed political change and even felt relief at his departure—but not in this manner. What has unsettled many observers is the sense that the United States has attempted to “fight fire with fire.” This outcome is not what most Venezuelans envisioned, including those within the political opposition familiar to Western audiences, such as supporters of María Corina Machado. Although opposition figures like her openly invited U.S. intervention, they anticipated a negotiated redistribution of power and benefits. Instead, it appears that they may receive very little of what they expected.

Vitalie: I saw today a screenshot from Trump’s own social media account presenting himself as the acting president of Venezuela. That raises a basic question: who is actually in charge right now? Venezuela briefly dominated the news, but ten days later it has almost disappeared from the headlines, displaced by Iran. Following different outlets, I’m encountering deeply contradictory accounts. If Trump’s intervention was meant to produce regime change—as many governments, including Moldova’s, rather naively framed it as a “democratic transition”—then it seems not to have happened. The regime appears to have reconfigured itself, with Delcy Rodríguez now acting as interim president. At the same time, some media report uncertainty and clashes, while much of what we see from the diaspora are celebratory images rather than serious analysis. There is very little credible reporting from the ground. So my question is: what do the sources you trust inside Venezuela actually say about who holds power now and how stable—or unstable—the situation really is?

Mariya: Not much, I am afraid. The accounts I follow tend to come from two polarized positions: either from people who actively support regime change and embrace it, or from people who passionately oppose it. The latter group has been highly visible at large demonstrations in Madrid, Buenos Aires, and Florida, which have been widely featured in international media. These locations, however, are hubs where relatively wealthy Venezuelans tend to migrate—often because they already possess passports, green cards, or pre-existing property and family or social networks. Many in this group also openly align politically with figures such as Trump or, in Argentina, Javier Milei.

By contrast, international media coverage has largely failed to capture the reactions of Venezuelans in Colombia or Brazil, where poorer migrants are more concentrated. It is therefore difficult to conclude that “Venezuelans” as a whole are happy with recent developments. My sense is that there is some degree of relief that Maduro is no longer in power, even if the future remains deeply uncertain and not necessarily hopeful.

Beyond this, it appears that, at least on the surface, the regime continues to function. There have been protests in major Venezuelan cities calling for Maduro’s repatriation, and the current governing structure still formally recognizes him as president. At the same time, it is extremely difficult to assess what is actually happening. Social media offers only partial and often distorted glimpses, while traditional journalism has been strikingly weak in terms of reliable sources on the ground. I have also heard very few Venezuelan researchers speak publicly so far—Alejandro Velasco being a notable exception—though several online webinars involving scholars and researchers based in Venezuela are scheduled for later this month. It may simply be too early, and mutual suspicion likely remains high.

One circulating suspicion is that the Rodríguez siblings, Diosdado Cabello, and others close to Maduro were negotiating a controlled and peaceful exit for him, alongside a regime reconfiguration that would satisfy Trump’s preference for an autocratic but cooperative power on the ground. According to Federico Fuentes, an Australian-based political economist who lived in and worked extensively on Venezuela, Trump may already have lost confidence in the opposition—even before María Corina Machado failed to deliver him a symbolic “Nobel Peace Prize moment.” There appears to have been a growing belief that the opposition could neither win elections nor sustain power, and that any US grip on Venezuela’s economy and political legitimacy achieved through them would therefore be unstable. From this perspective, elements of the Maduro government may have emerged as a more viable partner—so long as they complied with US demands. At present, it appears they are doing exactly that.

What interests me most now are a few surrounding dynamics. One is why it was deemed necessary to physically bring Maduro onto U.S. soil. I interpret this partly as an attempt to address a domestic legitimacy crisis within Trump’s own administration, unfolding amid the release of the Epstein files, the rise of Zohran Mamdani as New York’s mayor-elect, and the heightened visibility of violent ICE operations. Internationally, Trump’s failure to rapidly resolve the war in Ukraine—within the 24 or 48 hours he had publicly promised—has likely intensified the need to demonstrate decisive action elsewhere. Venezuela, in this sense, represented a relatively low-hanging fruit. While some MAGA supporters expressed anger, constituencies aligned with figures such as Marco Rubio were clearly pleased to see regime change materialize. Trump, it seems, needed a trophy—something concrete to signal power and effectiveness.

The second dynamic concerns the persistence of authoritarian structures within Venezuela itself. Even with Maduro’s removal, these structures remain firmly in place, making it difficult for dissenting voices to emerge. In such a volatile environment, it is unrealistic to expect overt criticism, particularly from those who remain dependent on the regime—whether for survival, access to resources, or even the possibility of leaving the country in a future wave of migration.

Finally, what I find striking is the sudden proliferation of “experts” on Venezuela. At the moment, it seems that every academic, political activist, or commentator has more to say about the country than those who have lived and worked there over the long term. I am especially hoping to hear more Venezuelan voices—representing a diversity of political positions beyond the familiar binaries of opposition versus regime—in order to cut through the growing white noise in international media coverage.

Vitalie: I have two related questions. First, drawing on your FocaalBlog piece about the (im)possibility of a left-wing critique during Chavismo: what would a viable left position on Venezuela look like today, given the local, regional, and geopolitical complexities we’ve discussed? Second, Trump’s recent rhetoric about the hemisphere—most dramatically his talk of annexing Greenland—seems to have reshaped the global frame and pushed Venezuela out of focus. How does this emerging geopolitical order affect Venezuela’s position, its relationship to countries like Cuba, and the broader future of Latin America?

Mariya: On the question of the left, the situation is deeply complex—and the left currently finds itself in a complex situation on multiple fronts. For some time now, parts of the left in the Global North have lost interest in Venezuela. This is partly due to their recurring tendency to shift attention toward newer, more hopeful, or more exciting left projects as soon as contradictions emerge in existing ones—particularly when those contradictions become uncomfortable.

Yet, coming from a region like Eastern Europe, where the left has had very little to be hopeful about over the past thirty years, I am less inclined to lose hope. I am thinking of the example of the Ukrainian left—or at least parts of it. Rather than making grand gestures aimed at resolving abstract questions of which big power wanted what and where, we might instead focus on the concrete effects of this power grab and the new political conjuncture on labor, class relations, and capital. We should be asking how the new balance of power affects communities, workers, and organizations on the ground. And also, how this conjuncture opens up new cracks in capitalism and new opportunities for solidarity—not only at the national level, but internationally, in ways that might enable structural change. These are the kinds of questions, I think, we need to be asking not only about Venezuela, but also about cases such as Iran.

Instead, much of the dominant discussion remains trapped at geopolitical level where the left has no political clout or impact, but many left commentators are trying to give the final verdict e.g. if the people on the streets of Caracas or Tehran are pro-U.S. or not. On the left, this often leads us back into old Cold War divisions. On one side are those who seek to provide analysis while also pursuing practical forms of solidarity with those who survive under existing regimes. On the other are those who are willing to support even autocratic governments that produce humanitarian crises, as long as this sustains their vision of a multipolar world. This latter position is often accompanied by a readiness to blame the US for every difficulty that socialist experiments like Venezuela has faced, declaring autocrats like Maduro “pure socialists” even in 2026, and to accuse critics of purism. Yet this, to me, is itself a form of purism: a blind attachment to an ideal that has no meaningful manifestation on the ground.

What we need instead is to finally understand mistakes from the past and start working to a socialism capable of confronting its own contradictions. A socialism, that can receive and address critique and reform itself from within, rather than morally and materially collapsing while clinging to familiar forms and waiting for capitalism to deliver its final blow.

My concern is that we are now witnessing an ever-deepening polarization on the left around these issues. Meanwhile, neither side of this divided left is actually in power, nor even in a position to meaningfully influence majorities. For this reason, I am far more inclined to engage in difficult forms of solidarity work—to listen carefully and try to understand people who do not necessarily come from my own political tradition, and to search for what might still bring us together. This is one of the reasons I have been trying to understand the Venezuelan diaspora more closely: to ask why so many people who were previously aligned with, or benefited from, Chavismo moved away from it; why some have even shifted toward the far right; and why they came to fear what they imagined “socialism” on the ground would entail. I do not yet have definite answers to all these questions, nor clear-cut solutions to their broader political implications. But I am convinced that the left cannot move forward without doing this groundwork with communities that have drifted away from it. And the time available to do this work is rapidly running out—we are working against the clock.

Looking more broadly at Latin America, the former Pink Tide is currently facing a strong right-wing resurgence. This is partly a response not only to dissatisfaction with more authoritarian regimes such as Maduro’s, but also with democratic left governments. In Chile, for instance, Gabriel Boric’s united left-front government lost the constitutional referendum and ultimately political power. This is a sobering illustration of the challenges faced by the left in government. At the same time, we are witnessing the possible return of Jair Bolsonaro in Brazilian politics, and Javier Milei remains popular in Argentina. In the wider regional context, Colombia and Mexico are the only larger countries currently governed by left-leaning administrations, and Trump has already signaled his intention to take measures against both. Under these conditions, the prospects for a revival of the Pink Tide appear minimal. But what is still worth examining are the remnants and legacies of those political projects on the ground. What continues to function despite regime change and shifts in political culture? Are there enduring cultures of solidarity, infrastructures of care and information, alternative media, or organizations fighting for specific constituencies and causes? And to what extent—and with what resources—can these elements help societies navigate the next period of global and continental hostility?

Finally, with regard to Cuba, we are largely left with speculation. Will China or other BRICS countries step in to provide the fuel and resources that Venezuela once supplied? Possibly not. A more hopeful scenario would be that Cuba steps up and accelerates the development of an alternative energy economy and reasserts its sovereignty in ways it has repeatedly managed to do under extreme scarcity. Yet, instead, we hear Trump framing Cuba as a done deal, already “sold out” to the US following embargo pressures and deregulation. Much will become clearer in the coming months. I am not especially hopeful, but I do think that the resilience of a small country like Cuba that never relied on fossil-fuel cash flows in the way Venezuela has always done, can still be surprising—and perhaps even humbling, particularly when compared to an extractivist model that has proven fragile both with and without US intervention.

Vitalie: Thank you. This feels like a rather bleak conclusion to our discussion. The collapse of the Pink Tide in Latin America mirrors, in different ways, developments in East Central Europe: the strengthening of right-wing sovereignism, illiberal democracy, and illiberal civil society. We studied at the same university, Sofia University, and I remember the hopeful 1990s, when human rights were assumed to expand rather than contract. My own politicization began in 2003, during the U.S. invasion of Iraq, and what struck me then—as it does now—was the silence of our authorities. We see the same pattern today, including on Venezuela: delayed, vague statements about a “gradual transition to democracy,” without substance. For a country like Moldova, this silence is especially troubling. If any state should be a strong defender of international law and a rules-based order, it is one that depends on them for its own survival. And yet, even here, the instinct is to wait out the storm.

Mariya: Maybe just one thing to say about international law. We are witnessing it being breached very openly today, but it has been breached for many years in our region—and now in Gaza to such an extent that what is happening should not really come as a surprise. I think we have to abandon the illusion that international law and human rights can still function as an agenda for equality and democracy if they continue to be interpreted so selectively, and deployed only in support of particular political projects and those in power.

Background image: Leonardo Fernandez Viloria/Reuters