The Romanian version of the article can be read here.

|

Floreana Fashion SRL is a textile factory in Moldova which has sewn clothes for several European brands. |

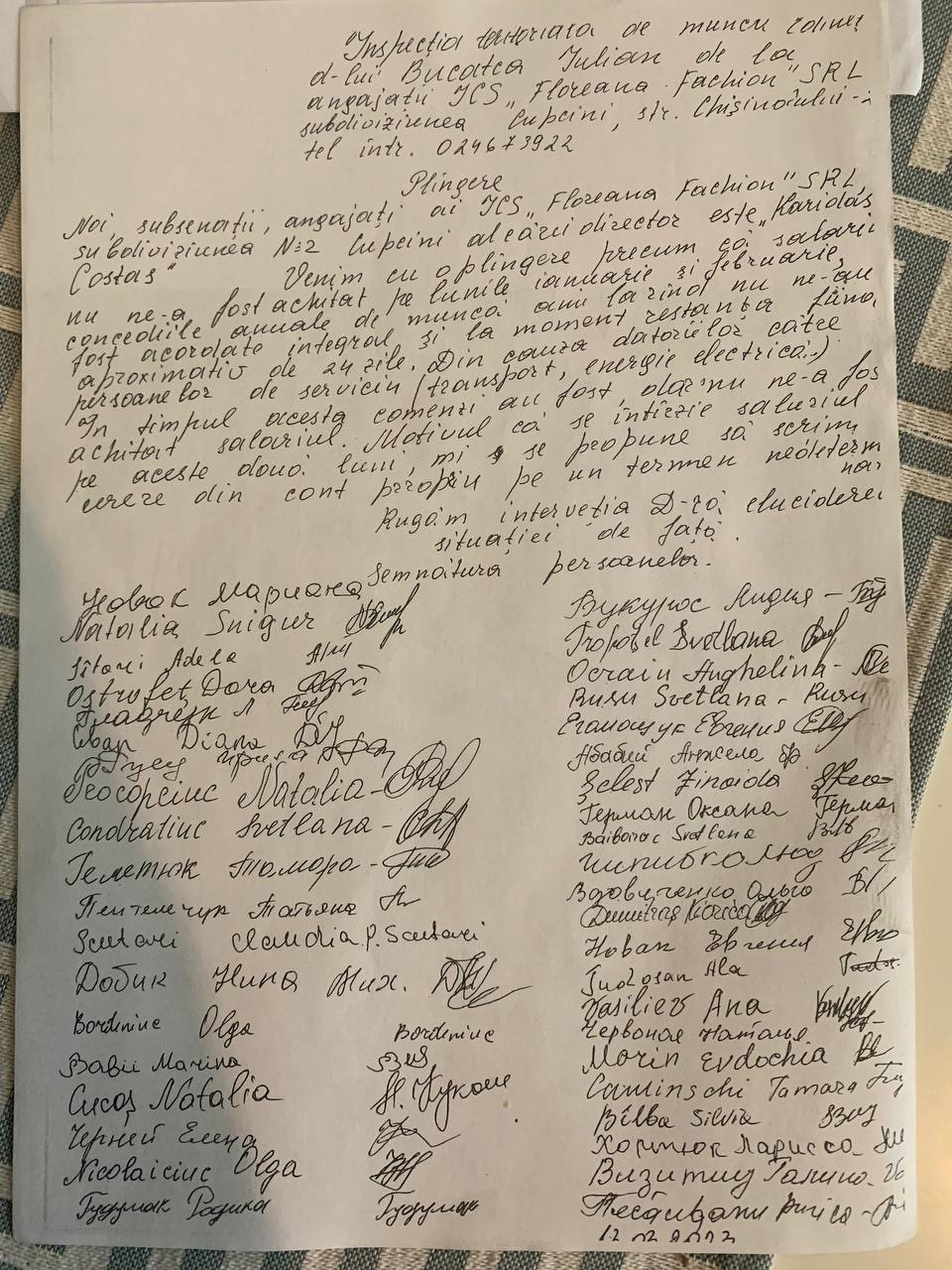

During the last 6 months, the workers of Floreana Fashion SRL have protested, have written collective petitions to the factory administration, to the Ministry of Labour and the State Labour Inspectorate, and some went went to court – yet so far, several hundred women employed at the five Floreana Fashion’s garment factories have not received their salaries for January, February and March 2023.

“We should receive our salaries for January, February, March and allowances for the unused annual paid leave days – these are large amounts. Nobody has received a penny…The employer has been telling us since autumn to go away because they have no requests for orders etc. We told him that any dismissal of the workers must be done legally and that we don’t want to just leave, nor do we want to write any request for dismissal on our own initiative.” (Personal testimony of a worker.)

1. About Floreana Fashion SRL and the problem of unpaid wages.

|

FLOREANA FASHION S.R.L. (IDNO: 1004601003137) was registered on 28 July 2004 in Florești. |

We found out incidentally about the fact that the employees of Floreana Fashion SRL have not been paid their salaries for three months when we read the news about the protest organized on 20th of March by the employees of the factory in Florești. The workers who organised the protest were saying that the management was forcing them to sign a request for unpaid leave…

A few days later we received, via the anonymous whistleblowing platform on labour abuses ida.md, a signal that workers from the Cupcini branch of the Floreana Fashion had not been paid wages for several months. Thanks to this signal and the communication with the workers which ensued, we were able to organize a meeting in the central park of Edinet with about 50 women, all former workers of the Floreana Fashion factory in the small town of Cupcini.

The building of the Floreana Fashion branch in Cupcini.

2. What did the workers at the Cupcini factory do in order to defend their rights?

It has been almost 6 months since these workers did not receive their wages for January-March 2023 and since they have been asking to be paid their wages and allowances for unpaid holidays.

In the meantime, as citizens of a country that claims to be democratic, the workers have resorted to the democratic instruments that the Moldovan state and society make available to citizens: appeals, letters and petitions to the competent bodies.

Back in March (on the 12th, to be precise), the workers sent a collective complaint to the Territorial Labour Inspectorate. In its reply the Balti Labour Inspectorate reported that the institution had carried out an unannounced inspection at the factory in Cupcini. As a result, a report was drawn up stating that the workers’ complaint regarding unpaid wages was legitimate. The employer acknowledged the arrears – amounting to 3 472 502 lei – in the payment of wages for January-February (the women had no way of knowing that March would also be unpaid!).

At the same time, TLI Balti issued a prescription to the administration of Floreana Fashion to settle all debts related to the arrears in the payment of salaries and leave allowances by 26 May 2023.

By 26 May, obviously, nothing had happened (apart from the fact that the workers continued to write to the factory director and administrator, the State Tax Service, the State Labour Inspectorate, the Balti Territorial Labour Inspectorate, the Ministry of Labour and Social Protection, the Public Prosecutor’s Office).

Each response from the responsible institutions reminds workers that they have the right to take their case to court individually and on their own.

3. What did the factory management do to pay their wage debt?

The management of Floreana Fashion SRL stated that it did not have the resources to pay the workers. The management allegedly put some of the factory’s assets up for sale in order to be able to pay the wages.

Curiously, according to the Floreana Fashion SRL administration, the company’s accounts had been blocked as early as January 2023…

It was exactly in January that the salary arrears started, although all this time, from January to March, the factory management said it had orders and the workers were going out to work.

So throughout February, Floreana Fashion management knowingly lied to the workers and fed them promises that they would pay the workers when the company’s accounts were already frozen. The women nevertheless were working and producing clothes…These clothes are now being sold secretly by the company and its “satellites” (more about this see below).

Why did the factory management continue to benefit from the employees’ free unpaid work for another 3 months, knowing that all the company’s accounts were already blocked?

Simply put: because it avoided taking legal responsibility for the employees at the factory and because it avoided paying the money it would have had to pay if it had terminated the contracts at the employer’s initiative. And also because they knew that no punishment was likely to await them. Who cares about employees’ rights in Moldova anymore?!

“The employer has been telling us to leave since the autumn because they no longer had orders. We told him that we cannot just leave. If they wanted us to leave they should dismiss us legally, by cutting staff or otherwise. Also they could inform us about the dismissal 2 months in advance, as required by law, and make all the necessary payments to us. The administration saw that we didn’t want to leave on our own and started to do something else: to send workers from Briceni and Draganesti on forced unpaid leaves, which probably haven’t been paid even today. One week they would call the workers to work, then they would send them back home again. They started this strategy with the two small factories, then with Târgul Vertiujeni and after this, they tried this kind of tricks with all of us.” (Worker, Cupcini).

4. The factory has no money to pay the wages but secretly continues to sell the clothes sewn by the workers.

Workers at the Cupcini factory told us that over the years the factory has been sewing some personal merchandise for the factory administration using designs and fabric from the orders of various brands.

“With every new order, from the leftover fabric we were asked to sew merchandise for him (the manager). I mean for him personally. For example, we sewed Julia Allert trousers and dresses. Although he isn’t allowed to steal the pattern, he asked us to sew some additional clothes and sold it elsewhere. At the moment the first floor of the factory building in Cupcini is full with this kind of merchandise. I told him that if he sells, he must have money and therefore he should pay our salaries.” (worker testimony)

This merchandise is stored in various locations, including on the first floor of the Cupcini factory, and it is still being sold on a daily basis at a shop in the center of Chișinău (on Ismail street), as well as at regular fairs organized in various cities around the country.

(Need we mention that the workers have not yet received a single penny of the factory’s debts to them, even though the factory sells clothes produced by the unpaid labour of the workers?)

Such a fair was organised on 4-6 August at the Jolly Allon Hotel in Chisinau.

The announcement says: Sales of clothes for women

We went on August 5 to the fair at Jolly Allon.

Everyone looking for clothes at Jolly Allon was following an ad posted on instagram by the company Criss Collection announcing the opening of a women’s clothing fair on August 4, 5 and 6 with “total discounts”.

The fair was taking place on the ground floor of the hotel, in the wing reserved usually for business conferences…In the large room 3 women sat at a long table and in front of them 6-7 rows of clothes: dresses, skirts, pajamas…

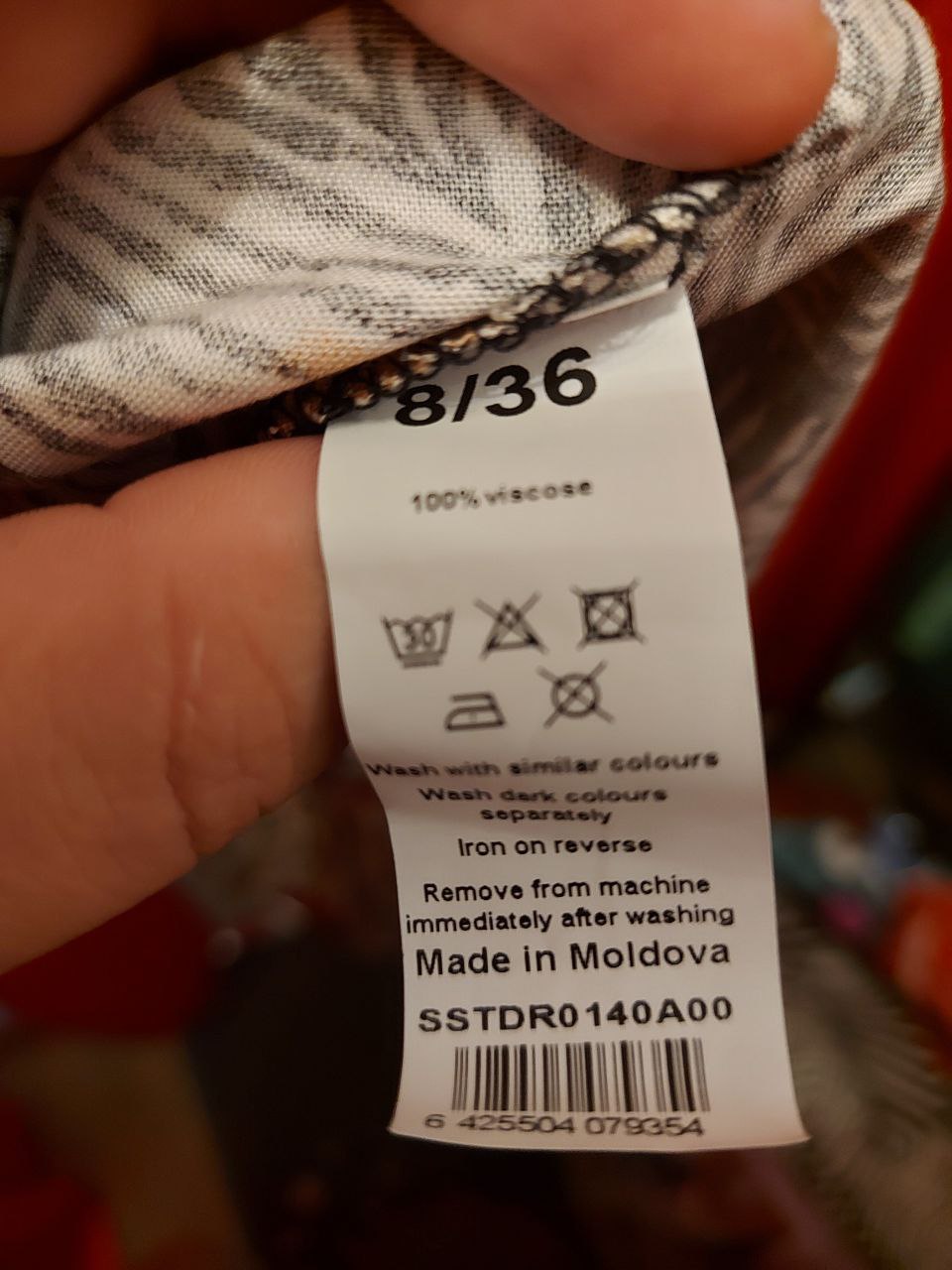

We enter the hall and start rummaging through the rows. I know what I’m looking for – the collar tags with the brand name. The collar tag was cut off most of the clothes. In some places, the coat was cut off along with the label.

The saleswomen are very thoughtful and attentive, approaching each buyer and telling them that if they need a size, they should look for the label inside the garment, the ones that indicate the composition of the garment, where it was produced, and sometimes the brand for which the garment was produced…

We touch the clothes pretending to be interested in buying something. We take them from the shelves, smooth them out, open the buttons, put them on the body and look in the mirror at how they fit…Then we look, as if disinterested, at the labels…

Under any other circumstances, the Jolly Allon fair would be an extraordinary luck for anyone: here are gathered together branded clothes that you can possibly find in Ireland or Great Britain, but not in Moldova… Alison Hayes, Wallis, Primark, George, F&F, Asos… Some better known, some less known, but all equally inaccessible in Moldova. And they are extremely cheap.

On some merchandise the label says – “Made in Moldova/Fabricado en Moldavia” and even in Indonesian – “Buatan Moldova”.

We try on a few clothes and we buy two pieces in order to have a receipt and a proof of purchase.

It is clear that the organizers are selling clothes they have no right to sell.

(But we care very little about the fact that a Moldovan company would “illegally” sell clothes that would belong, as intellectual property, to other companies. We are mostly concerned about the fate of the workers who remain unpaid to this day.)

We sent some photos of the clothes to a worker and she confirmed that they were sewn by Cupcini workers…

“I remember how I sewed some of these dresses – wearing gloves and in extreme cold. I was freezing in the winter. Imagine: two-story building without heating. There were several fan heaters that were blowing the air and that was it. Near them it was warm while in the rest of the room it was cold. The temperature was 11 degrees Celsius and that’s how people worked. Some of the women were even wearing gloves. Additionally, there was mold everywhere.”

We ask: But didn’t the inspectors (e.g. the Public Health Agency) come there to check the state of the building?

The worker replies: They came, but they were of no help. They were allowed to take as many dresses as they wanted and closed their eyes on all the violations.

We don’t want their millions, we just want our wages, she says and bursts into tears.

The payment of wages on time and in full is a fundamental right of employees.

What’s more, breaking the agreed terms for paying wages qualifies as forced labour. And forced labour is forbidden! (Article 7(4)(a) of the Labour Code).

Under Article 146(2), persons responsible for not paying wages on time are liable to disciplinary, material, administrative and criminal liability.

According to Article 330 (2), in case of withholding, due to the employer’s fault, of the salary, leave allowance, release payments or other payments, the employee shall be additionally paid, for each day of delay, 0.3 percent of the amount not paid on time.

5. What have state institutions done during these 6 months to protect workers rights?

The Balti Territorial Labour Inspectorate carried out an inspection at the factory on 24 March, registered the violations signaled by the workers and issued a prescription to the factory management to remedy the violations by 26 May 2023. This deadline has already expired 4 months ago. No conventional liability action against the factory followed. However, the Inspectorate informed that in the event of failure to remedy the infringement within the deadline, the Balti Territorial Labour Inspectorate would draw up a report on the infringement in order to hold the management liable under Article 57(1) of the Contravention Code.

The Edinet District Prosecutor’s Office said that it was not within its competence to investigate a labour dispute, although there were clear signs of economic fraud in the case. The factory management, using a third party company, continues to sell the merchandise from the factory’s warehouses. This merchandise is produced from fabrics left over from various orders placed by brands. The merchandise was sewn and sold in breach of the terms of the contracts between the factory and the brands. This is merchandise for which there are most likely no documents of origin. Moreover, the merchandise was sewn by workers that were not paid for this work.

The State Tax Service considered that it was not within its competence to intervene because it was a labour dispute. Although the workers indicated in their complaint about systematic violations of the tax code at the company. For years, the company was declaring only the base salary to the State Tax Service (while the full salary could be up to twice the base salary).

In their replies to the collective workers at the Floreana Fashion factory in Cupcini, the Ministry of Labour and Social Protection, the State Labour Inspectorate, the Balti Territorial Labour Inspectorate and the Edinet Police Inspectorate recommended that the workers go to court to restore their rights.

The women feel that state institutions are passing the responsibility from one to the other and that they are generally on the side of the company. And it’s hard to prove them wrong when the string of complaints, letters and appeals have had no effect (so far) other than other responses, appeals and redirections, and no public institution has taken on the role on being an active advocate for a group of women workers who have been duped by a group of businessmen.

No institution has tried to assist these women along the way. At least to inform them that the free state legal aid service exists and that they could benefit from the free assistance of a lawyer to represent them in court.

Initially, the women workers wanted to go to court collectively, but they couldn’t find the financial resources to hire a lawyer to represent them.

“At the prosecutor’s office they gave us the number of a Lawyers’ Office. We called them to discuss the price. We said there were so many women from the Cupcini factory and together we could raise about 12,000 lei. The lawyer told us that he wouldn’t do any work for those pennies.” (worker)

Therefore, out of all the former employees of the Cupcini factory, only a few women have found the financial resources to pay a lawyer to represent them in court.

A lengthy court case will most likely follow, but hopefully these few women will eventually receive their hard-earned wages.

But what will happen to the other dozens of women at the Cupcini factory alone and hundreds of women at the other branches of the factory who don’t know how to go to court and don’t have money for a lawyer?!

6. What about the brands? Do they hold any responsibility for the workers sewing their clothes?

The garment industry is organized in complex global supply chains, where brands usually don’t own any factories. Therefore, brands like Alison Hayes, Wallis, Primark, George, F&F, Asos – which used to sew their clothes in Floreana Fashion factories – are outsourcing their production in countries with cheap labour – like Moldova. Brands decided to outsource in order to minimize the cost of the production, to increase the profits and not to be responsible for the working conditions of the workers sewing their clothes. Smart move! But it doesn’t absolve brands of their responsibility towards workers.

“According to international standards, brands retain a clear responsibility to prevent, address, and mitigate adverse human rights impacts for the workers at the factories where they have their clothes produced. The UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights (UNGPs) were established to address the pervasive problem of global companies outsourcing production in order to evade legal responsibility for the consequences of their business practices.” (2)

Although, according to the international standards, brands are responsible for the workers across their supply chain – they rarely are accountable for their workers. You know, like ensuring that the safety and health standards are respected or that the workers are being paid a living wage, or being paid at all.

In the case of Floreana Fashion factories, workers stated that brands used to send an audit company every year to check how the factory and the workers were doing. Guess what?! Apparently, the audit company never talked to the workers and they never saw the mold on the walls or the fans that were not working. Although, there were clearly unsatisfactory working conditions and labour rights abuses for many years.

This is by far an exemption, a 2019 report of Clean Clothes Campaign exposes how the social auditing industry protects brands’ reputations rather than workers’ lives and thus fails workers by design (3).

7. What else can be done?

In some countries – Romania (4), for example – the legislation provides for the creation of a Guarantee Fund for the payment of salary claims in the event of insolvency.

Such an initiative was also proposed in 2018 in Moldova by the National Confederation of Trade Unions (NCTU) but it was not supported by the parliament, instead the parliament suggested that the NCTU should negotiate it with the Business Association.

In other words, 5 years later, the situation remains the same: workers remain unprotected in cases of insolvency, the trade unions promote the initiative and the governments successfully boycott, through their unwillingness to intervene, the creation of such a Fund and urge the trade unions to somehow come to terms on their own with the employers.

REFERENCES:

1. Chebeleu Ioana Camelia, Micula Ioana Alexandra, Luca Iulia Delia, Sasu Ecaterina, Gligor Loredana. Lohn’s Contract.

Source: https://protmed.uoradea.ro/facultate/publicatii/ecotox_zooteh_ind_alim/2022A/Papers/11.%20Chebeleu.pdf

2. https://cleanclothes.org/faq/responsibility

3. Clean Clothes Campaign, Fig leaf for fashion: how social auditing protects brands and fails workers, 2019 https://cleanclothes.org/news/2019/we-go-as-far-as-brands-want-us-to-go

4. Legea nr. 200/2006 privind constituirea şi utilizarea Fondului de garantare pentru plata creanţelor salariale.

Text and photos: Lilia Nenescu (anthopologist, legal counselor on labour rights), Vitalie Sprînceană (sociologist).

Featured image: Octavian Fedco.

[…] Som fx i tekstilindustrien, hvor europæiske virksomheder lukrerer på lave lønninger, og hvor faglige aktivister har ført langvarige retssager om løntyveri. I mindst én veldokumenteret sag måtte over 100 kvinder kæmpe i to år for at få udbetalt den løn, de havde til gode. […]