The Romanian version of the article can be found here.

What is the fate of global democracy in an age of populism, white supremacy and financial control over the global economy? And can we even hope for democracy on our small piece of land?

Let me start this reflection with a bitter truth – NO country in the world today is a democracy. We can talk about it, we can do things in the name of democracy, but the reality is that we are experiencing a mere scrap of what true democracy is. The Western world is living in what sociologist Eva Illousz calls imperfect or partial democracies.

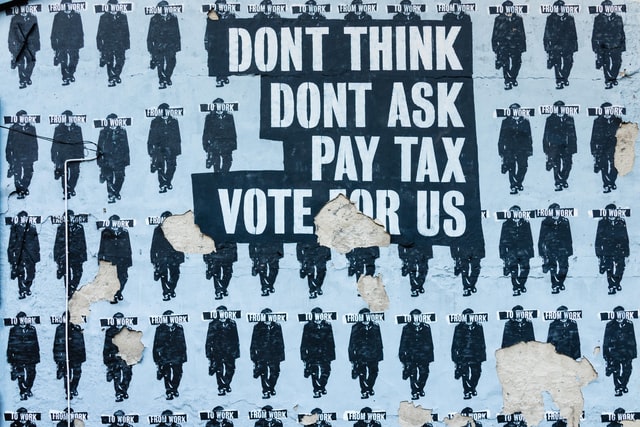

The successful illusion of democracy globally comes from either not understanding what it is or mistaking it for something else.

What is democracy and can we ever achieve it?

When nearly every country calls itself a democracy, from the US to North Korea, not only the definition of democracy becomes mutable based on who happens to talk about it, but the trust people hold in democracy and democratic processes becomes eroded.

Etymologically, democracy means the rule of the people – from Greek, the people (demos) hold power (kratos). In other words, the idea is that ordinary people should have meaningful influence over how the society they live in is being managed. But even within this explanation, a number of philosophical, as well as practical questions, arise:

Is democracy a means or an end? If it is a set of outcomes, what if they can be achieved through different means?

When we say “the rule of the people”, who counts as “people” and what is the extent of their “rule”? Ancient Athenians are often referred to as the forefathers of democracy, but let us remember that slaves and women did not count as “people” and did not participate in assemblies. Democracy and what counts as “people” therefore evolves and expands to include previously marginalized groups.

Today, the rule of the people is limited to electoral politics. But even within electoral politics, the influence of the people has diminished considerably over the last decades. Decreasing voter turnout is a proof of how little influence we think we have over major decisions in our country. And the decline of trust in political representatives are proof of our disappointment with the systems of power and how they are run.

The illusion of “people” power

The influence of ordinary people on politics has diminished considerably the moment financial capital consolidated its power and influence. The neo-liberal expansion resulting after Bretton Woods, gave global finance a green flag to do whatever it pleases not only within the limits of nation states, but internationally.

Global capital is not bound by nation-states and has nearly an unchecked power to shape public policy with no concern to what citizens really want. It is therefore not subject to effective democratic control and can dictate policy through threats of capital flight.

In 2017 Amazon announced it wants to open a second headquarter asking potential host cities to present their offers. The corporate giant promised jobs, infrastructure, and investment to whichever city will advance the most attractive offer. The announcement started a bidding war among states who were fighting in their bids for the lowest taxes and most attractive legal environment – for instance Maryland approved a $6.5 billion package in subsidies. In other words, Amazon promised investment and jobs, but first asked the state for the money to provide those.

In 2018, Deliveroo, a food delivery platform, forbade its couriers to work as part of a worker cooperative in Belgium. The couriers were forced to work ad hoc with no social security benefits. It was a political choice to favor the gig platform over workers’ rights and free it from labor law.

These examples and countless others reveal very clearly how global capital transforms democracy into a joke, a buzz word with no substance. For when workers strike and demand unionization, and the law favors the corporation, how can we speak of the will of the people?

This brings us to the question of power. In a democracy, power ought to be in the hands of the people. Today, however, social fragmentation and proliferating authoritarian leaders are terrifyingly reminiscent of Plato’s Republic:

Tyranny naturally arises from democracy. The people always have some champion whom they set over them and nurse into greatness. … This and no other is the root from which a tyrant springs; when he first appears he is a protector.

The anger and injustice people feel is often misdirected from economic elites and their endless accumulation of capital towards the most vulnerable populations – migrants, refugees, anyone that can fall under the “other”.

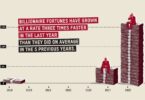

Today power is not in the parliament nor in the government. It is in places where we have no control over – in Central Banks, in International Organizations such as the IMF (International Monetary Fund) and the EC (European Commission). Power is concentrated in the pockets of the world’s 1%.

When over 60% of Greeks vote ‘Yes’ to reject the austerity conditions imposed by the IMF, European Central Bank, and the European Commission in the aftermath of the financial crisis, the government of Tsipras did exactly the opposite of what the people wanted and accepted a three-year-bailout with even harsher austerity conditions.

When people took over the streets of Caracas, Venezuela in 1989 to protest against austerity measures and unemployment, the government (elected on the promise of reducing austerity) caved in under pressures from the IMF and introduced price increases as part of the IMF’s relief package. These are only a few examples of the clash between the will of the people and the interests of global finance.

In most developing nations worldwide decisions about privatisations and economic reforms are taken behind closed doors after consultations between international institutions that have no people representation and a group of national technocrats representing the government.

In the light of a neo-liberal world order, democracy, Peter Mair argues in his book Ruling the Void, has been replaced by a technocracy which appeals to “expertise” in order to override any claims to democratic legitimacy. These experts see everything through a cost-benefit lens and aim for “efficiency”. And in the eyes of “efficiency”, social welfare is another number in the accounts that can be reduced.

Popular (mis)understandings of democracy

In her documentary What Is Democracy?, Astra Taylor asks ordinary people what they think democracy is and what they think undermines it. People often answer that democracy is “freedom” – to exercise consumer choice, to live with no fear, to do as one pleases (italics added). At the start of the current pandemic, people were often revolting against masks and restrictions as violations of their freedoms and rights. Today people are worried about vaccine requirements as being undemocratic.

It all revolves around the “I” and “my freedoms” even though one person’s freedom limits that of another. This “me, myself and I” talk is the result of neo-liberal thought protruding every cell of our modern society. Freedom and by extension democracy have come to be understood as the state of independence, and not interdependence, for interdependence means recognizing that our needs are met by the society we live in, a society we all contribute to.

Industrial and financial capitalism alters the meaning of freedom so that it focuses on “free labor” and “free choice” in the marketplace. We are “free” to sell our labor and we are “free” to buy what we find on the shelves of a supermarket. Rarely do we question our lack of influence over what we buy, how it is produced or how we work.

We are completely powerless in the economic sphere. We don’t contribute to decisions about how our country’s budgets are allocated, we can’t influence how government subsidies are distributed, we don’t choose the investment areas of our domestic economies. We can gather on the streets and protest against oil and the next subsidy will still go to Shell.

And, most terrifyingly, we have no control over our work – the place where we spent most of our lives. We seem so sensitive about our freedom in relation to the state, but we happily accept coercion in the workplace and the authority of our bosses. Employers can dictate how we dress, how we present ourselves on social media, when we should come to work and when we should leave, or even refuse us bathroom breaks as the terrifying stories from Amazon’s warehouses testify.

We want democracy in the political sphere, but we have no problem with accepting a dictatorship at work. This inconsistency is the result of a successful neoliberal campaign to detach politics from the economy. Technocracy managed to insulate the management of the economy from popular pressure.

As Steven Miles argues in his brilliant work The Experience Society, democracy in a neoliberal context has effectively been reinvented as the ability to consume. This consumer society successfully convinces us that not only consumption is a “natural” state of affairs, but that it also gives us freedom, a sense of belonging and the opportunity to express ourselves. But consumerism can’t replace the lack of agency we feel over our work and lives. For Marx, capitalist ideology was exactly this combination of commodity fetishism and alienated labor, derived from disconnect and loss of control over the consumer society we live in.

Consumerism and commodification of everyday life managed to distort our understanding of democracy. It gives us the illusion of choice, but our reality resembles more an Orwellian scene. We are fighting for this or that freedom, for this or that right within a system that remains unchallenged. We can choose what to buy, but it seems we have close to no alternatives for how we want to organize society.

Does Democracy Stand a Chance?

As long as there is a huge gap between the rich and the poor, democracy cannot stand. As Aristotle says

“For when some possess too much, and others nothing at all, the government must either be in the hands of the meanest rabble or else a pure oligarchy.”

Even Adam Smith, the proclaimed father of capitalism said that those who control the economy will use their money and influence to control the political system. To overcome the incompatibility between capitalism and democracy we need to either make our political system undemocratic or run our economies in a democratic way.

Firstly, we need a radical expansion of democracy into the economic and judicial spheres.

Workers should be able to control how they work, consumers should have a say over what is produced, and communities should be able to influence how things are distributed.

In the Brazil of the 80s and 90s, community projects to address poverty and social problems, rural movements fighting for access to the land and worker unions fighting for workers’ rights converged in building the solidarity economy that during Lula’s presidency was included in public policy. A social forum as a platform for discussions about fiscal policy, national strategies and regulatory framework was integral in ensuring a participatory process.

In our own Moldovan context we need to bring the issues currently discussed and solved by techno-oligarchs and external “experts” up for public discussion. Citizen assemblies could provide a platform for ordinary people to engage in discussions and debates about fiscal policy, economic regulations, allocation of resources to education, health and culture, as well as prioritization of productive lines.

Worker cooperatives is another example of democratising the economy. Mondragon is one of the largest worker coops globally and a good example of a first step towards organizing the workspace democratically. Unlike a capitalist corporation, where all the profits flow back to the shareholders and workers have almost no control over how the company is run, in a coop, workers are the owners and participate in all important decisions from production to allocation of profits.

As Astra Taylor writes

“Formal political equality, exemplified by the right to vote, is not enough to ensure democracy, as the wealthy have many avenues to exert disproportionate power. Extending democracy from the political to the economic sphere and saving democracy from capitalism is the great challenge of our day.”

And secondly, we need to find a way to rebuild our trust in each other.

Our society is so fragmented and so used to pointing fingers that having participatory democracy without the ability to engage in critical dialogues could turn into a disaster.

The best argument against democracy, said Churchill, is a five-minute conversation with the average voter. Democracy is intellectually hard. It requires both structures and popular sensibilities to be able to persist and thrive. The paradoxical question is what comes first: the society and institutions that mold democratic citizens or citizens who are able to create such a society?

We do need to work on these two fronts concomitantly. Our critical situation and our endless social problems will unfortunately not be solved by the win of any political party. As long as the systems we have in place are inherently corrupt, dysfunctional, and undemocratic, we can’t hope for a light at the end of the tunnel in these upcoming elections. Vitalie Sprinceană writes here in more detail about how we could restart our Moldovan political system from scratch.

And at the same time we need to find ways to engage citizens in political discussions and debates beyond political TV shows, mean Facebook comments or a tick on the ballot box.

In today’s reality, the ancient Athenians belief in the power of the people and their system of lottery to determine who would rule, seems insane. Indeed, when each of us is presented with a personalised feed that affirms our perceptions of the world, and our fired up emotions and engagement are used for profit making, it is hard to speak of critical thinking.

Nevertheless, we do need to rebuild our trust in each other and in democratic participation if we ever want to overcome the many challenges we are faced with today. Democracy may be only an ideal, subjected to continual examination and scrutiny, but it does not mean we shouldn’t strive for it.

“To improve is to change, to be perfect is to change often.” (W.Churchill).

Featured image: Pawel Czerwinski on Unsplash