The Romanian version of the article can be read here.

2021 marks 30 years after the end of the Cold War but here, at the edge of Europe to the East, it feels colder than ever.

A strip of land between the EU and Ukraine, Moldova carries the imprint of the cold war to this day. If during the Soviet Union the Cold War was marked by a nuclear threat, today, the ideological conflict between the US and its allies and Russia and the post Soviet bloc takes a form of economic sabotage that is as lethal and as destructive as military warfare. Political discourses make it seem that we have only two choices – siding with the EU or playing the Russian game. Even if some communication efforts encourage keeping good relations with both, in practice, economic policies favouring either of the two sides will upset the other, and the opinions of the public remain divided. Perhaps politicians should spend less time courting international “partners” and more time listening to the people and making efforts in uniting the country, not exploiting its divisiveness.

However, this divisiveness comes from a difference in desired strategy, not in desired end goals. For what we ultimately want to achieve is the same, and is what unites us. Everyone wants a better quality of life, decent salaries to sustain a dignified life, access to good healthcare and good education. Everyone wants to see the end of corruption and have a class of politicians that do their jobs and work for this country, not subjugate it to their own financial interests.

We have common goals, but we are divided in our beliefs in the paths that would best serve those goals.

The previous president was convinced he could maintain good relations with both East and West. His continuous flirtations with Russia and its allies, however, on top of his lavish lifestyle show an obvious preference for the Eastern oligarch class. His belief in a development path fueled by joining the EuroAsian Economic Union is also questionable. Looking at the ex-Soviet bloc, we see a bitter prevalence of poverty, authoritarianism and corruption, so naturally people’s hopes turn to the West.

Our cry for help is louder now that COVID-19 has brought havoc to our already vulnerable economy and the consequences of this crisis are yet to be felt. We are in a very cruel position where the only hope seems to come from outside. And from the looks of it, we favor the foreign wind blowing from the West.

The new president is already building bridges to the West and our confidence in Europe only consolidates as we see these bridges bringing in some results. The EU has committed 15 million EUR to help Moldova combat the effects of the pandemic and we can only expect more collaboration happening in the future.

We remain only to ask ourselves what is the cost of this and future gestures from our Western development partners. For a lending hand from the West always comes at an enormous cost.

***

If the EuroAsian Economic Union is directed by the Moscow hand, the EU’s foreign policy is largely guided by the Washington hand. It would be far too naive to believe that Europe or the US for that matter are neutral in our case. History tells us otherwise. Big powers in both East and West have big geo-political appetites. We ought not forget that the wealth enjoyed by Western countries today is largely a product of centuries of colonialism, exploitation and genocide of indigenous people everywhere on the planet. The fact that the West stays wealthy to date comes at the expense of low income countries who continue to be exploited. Developing countries accepting a lending Western hand are forced to yield to the neo-liberal global order, adopt so-called “free market values” and implement restructuring programs imposed by aid organizations such as the IMF and the World Bank. The numerous examples of developing countries in Africa and Latin America dependent on Western aid show that this intervention does more damage than development. It is just another form of imperialism disguised as assistance.

If we take the example of Pakistan, a country that gained its independence shortly after WW2, it was bailed out by the IMF 22 times, 15 times of those since 1980 alone. Seventy years of intervention with no significant development raises serious questions about what exactly is perceived as development by these organizations. In the case of Pakistan, the path to “development” was paved by privatizing state-controlled industries, removing protectionist subsidies, increasing taxes, intentionally slowing the economy, and implementing austerity cuts to public programs. To put it in simple terms, it meant auctioning domestic state industries to ultra rich foreign investors that seek to further expand their pockets. And this measure is not unique to Pakistan. The technocratic nature of the IMF means that it can export these solutions to virtually all developing countries applying for their aid, regardless of national context, people’s beliefs and values.

The World Bank is not different in that matter. Marketed as a hope for sustainable development, the bank like other international financial institutions, puts the profits of a few over the livelihoods of many. Investments from the Word Bank between 2004 and 2014 displaced 3.4 million indigenous populations, who, forced by the military out of their homes, became refugees. This pivot to privatization favors only the foreign investors, not the public population who are denied – in the name of ‘development’ – access to healthcare, water, and education.

When the Global South refuses to bend to the will of Washington and pursues support from other countries or takes an independent path, the US meets them with economic austerity or military intervention. There are too many cases of US aggression in Latin America, the Middle East, Sub-Saharan Africa, South East Asia and Eastern Europe. The case of Bolivia is particularly tragic. Evo Morales, a democratically elected indigenous president, has pursued exceptionally successful policies that reduced poverty by 42% and advanced progressive laws with regards to the protection of the environment – Bolivia is the first country to bestow rights to the natural world. His victory was fueled by a popular rejection of corporate globalization that deepened poverty and inequality in the country in the previous two decades to his presidency. His position and attempts to nationalize lithium, Bolivia’s natural resource used in batteries that power clean energy technologies such as electric cars, was seen as a threat to the US interests. Therefore, in 2019 it supported the violent military coup against Morales. This, and all the other coups backed by the US – in Iran, Guatemala, Congo, Dominican Republic, South Vietnam, Brazil – speaks for US exceptionalism and commitment to do whatever it takes to stay a global hegemon.

One need not look that far however to understand the consequences of Western intervention and foreign aid. The case of Greece within the EU itself shows how rich countries enforce austerity measures up to an economic default, making free way to financial capital at the expense of the majority of the population.

This should worry us. This should remove any naive dreams that the US or the EU would lend a hand to Moldova without any geo-political or economic interest.

***

Reading these lines, one might feel hopeless – if both ways, to the East and to the West come at great costs, what other ways are there? I am afraid, reader, I cannot offer a simple straight answer. If there were a third, better way, it would have probably already been on someone’s agenda.

My aim with this essay was not to give solutions. I only aim to remain critical and encourage you as well to ask questions, to demand clear communication from our government, and to look beyond flashy words like “European values” and “European path” that lost its meaning from being overused.

What we need more than ever in our political education is to remain critical and pragmatic. We need to break free out of the dual discourse emphasized so much in our politics. Nothing is good or bad. There is no such thing as West is good and East is bad or the other way around. We need to learn to navigate the much more complex geo-political environment by asking questions, by informing ourselves through the examples of other countries, by developing tolerance and empathy to finally listen to each other. And this final point is perhaps the most crucial – listening to each other. We don’t do that anymore. We jump to conclusions and we dismiss anything that does not match our own views.

So, dear reader, if there is one thing I would like to leave you with, it is this: listen to others. Listen to the opposing views perhaps even more attentively than to the opinions that match your own. Having different views is important. It keeps us inquisitive and it helps us keep our politicians accountable.

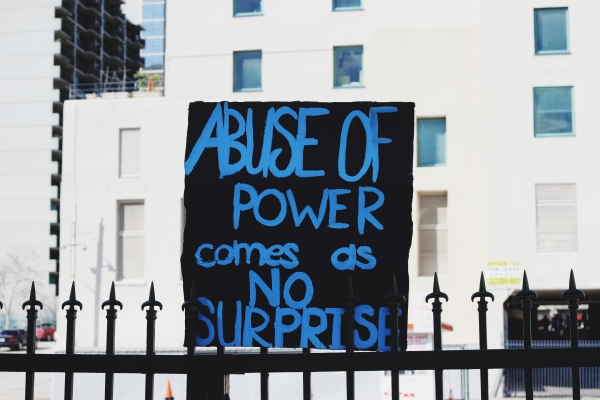

Photo by Samantha Sophia on Unsplash.

Maia Sandu’s messianic figure(head) as the saviour of Moldova for many (maybe too many) young people, whereas she is the archetypical neoliberal, is a bit paradoxal comparing to current anti-neoliberal momentum in youth politics around the world. A self-styled “socialist” Dodon once said that Moldova is a leftist country but Sandu’s victory shows otherwise. It seems that the rightist turn in Moldovan political landscape (PSRM was the only self-styled leftist party against a plethora of rightist political parties in last elections) reinforces the neoliberal “success” of three decades of “market economy” (capitalism) in Moldova despite the disastrous social consequences (and Romania is not better). I would like to read an analysis on why an alternative Left, distinct from PCRM or PSRM (and obviously from social-liberal PD), doesn’t have emerged in Moldova yet (I think of Slovenian Levica case) and why an anternative view of the future for Moldova distinct from the dualism between EU/NATO siren songs and ‘Russian friendship’ seems to be today unlikely.

Hi Kevin!

Great observation and this is something I want to investigate further as well. I think, in our country’s context, ideology is not so much addressed in political discourse nor in the media – if not at all. Sandu’s win was very much due to her promise to fight corruption (we have so many uninvestigated cases – including the famous stolen billion – and that our judicial system is compromised). I think most people attribute the disastrous consequences of neo-liberal policies to corruption and that if there were no corruption these policies would bring us the prosperity we all seek.

Of course, Dodon, what he says and what he does is nothing resembling socialism. It’s a form of oligarchy packaged into a socialist brand. And I think young people turn away from terms like “socialism” because they associate it with Dodon’s party, corruption, and to some extent to the Soviet Union as well.

From my own observations of what is happening in Moldovan politics, the debates and discussions are resumed to some trivial “she said/he said” types of dialogues. It’s a sort of gossip culture that really lacks substance. Most people also lack a strong political education and critical thinking so it’s easy in a way to divide people and keep them in this dual position – East vs West, our values vs their values.

I think seeing this chaos in politics and how every single one of them becomes corrupted at some point or another, demotivates young people from becoming politicians (we will near years to clean up the image of a politician, people simply don’t trust them). We do have some new parties emerging, but again because of the main media that belongs to political parties, they don’t have a lot of representation, and they lack the financial means to consolidate their positions.

That’s a very interesting topic and I will definitely dedicate one of my next articles to investigating the possibility of an alternative Left.

Thank you very much for your answer. It would be great an article about that. Moldovan politics is very interesting because of factors like the strong influence of geopolitical topics and a highly politicised Constitutional Court that they do not exist in others post-Soviet countries (without being member of EU and being a parliamentary democracy based on citizenship over ethnicity unlike Baltic States with their discriminatory State policy against Russian minority). Moldova is worth of study but there are few trustworthy sources: I only know this site with an interesting leftist viewpoint that I read with my basic command of Romanian language.